#KnowingTheirVoice

Although it has been some time since my last post, I want to continue the conversation on academic dishonesty. As mentioned in several of my previous posts, academic dishonesty is not a new phenomenon. However, there are few studies that provide a voice for the lived experiences of rural general education high school teachers regarding this phenomenon. It is the rural classroom teacher, with their unique insight into the complex challenges of the rural educational experience, which is best able to provide a voice for the lived experiences and perceived need for pedagogical change regarding academic dishonesty. My goal as the researcher was to turn up the volume on these voices.

A powerful theme to emerge from the data gathered during the interviews and the focus group session had at its core the student-teacher relationship. It was Payne (2013) who stated, “The key to achievement for students from poverty is in creating relationships with them” (p. 101). Similarly, Elmore (2015) described the 21st-century learner as one that “hunger[s] more for relationship than for information” (p. 48). Being a veteran of the classroom, I know that academic dishonesty is rare in classrooms where learning is relevant, engaging, and where teachers communicate with students, developing positive relationships. The reader could easily view this theme as the lifeblood of the previous themes I have shared.

The role of the classroom teacher cannot be understated. The key strategy in which the participants of this study gave voice to was that of relationships. Madison described this strategy well when she recognized, “I have found that by gaining a student’s trust and respect, that student will more often than not perform better academically in my classroom” (Interview, March 23, 2017). Going further, she stated, “In a way, I feel a student who is academically dishonest in my class is personally insulting me and damaging the rapport and respect we have built” (Madison, interview, March 23, 2017). This sentiment was not lost on the other participants.

In describing the development of the strategies to manage the academic dishonesty in the digital age, Hailee stated,

I try [to] put in new methods of teaching . . . I try to stay on top of that, but for me, it’s, it always comes back to that personal application . . . I thrive on personal relationship. (Interview, March 13, 2017)

Suzanne emphasized this as well, describing that when students do original work, “they have to give it their own touch, their own voice” (Interview, January 10, 2017). Elaborating, she stated, “I as a teacher have developed a . . . relationship with those students, so I know their voice, their quirks, their syntax, . . . strengths, and weaknesses” (Suzanne, interview, January 10, 2017). Abby equivocated, stating, “You have to know your students better [be]cause your like, ‘that does not sound like their work’” (Interview, January 24, 2017).

To foster such a relationship strategy, Emma explained, “[I tell my students], ‘This is a no stress class!’ And so, because of that, there is a closeness that occurs in our classes” (Interview, January 24, 2017). As she detailed, “In my class, they know me . . . there’s not a lot of distance between [the] teacher-student relationship in my class” (Emma, interview, January 24, 2017). As other participants put it, such relationship building enables them to “hear those conversations” (Chyann, interview, February 28, 2017) while “combating plagiarism . . . on the ground” (Sydney, interview, March 16, 2017). Hailee framed it as, “I try [to] lean on that, you know, that little bit of personal connection piece. And I think sometimes . . . that’s effective” (Interview, March 13, 2017).

Within the focus group, the participants once again put forth that the key strategy in which to combat academic dishonesty in the digital age was that of relationship building in the classroom. In reflecting how creating such relationships affected her pedagogy, Hailee stated, “I think that changes what you do in your classroom too. I give my kids a lot more grace” (Interview, May 1, 2017). It is this type of relational grace that Allie spoke of when she described telling her students, “So if you plagiarize, I actually don’t care as long as we can talk about why it’s plagiarism and you fix it” (Interview, May 1, 2017).

Not all the focus group participants found building relationships such an easy task. In reaction to the others’ discussion concerning this, Payton added:

Along those same lines, I don’t know . . . I’m in a rural school district and I understand that comment about you know the students – you know whose doing this, that, and the other. A lot of times I don’t. I’m clueless. (Interview, May 1, 2017)

However, he went on to say, “I’m thinking that’s something I maybe need to change. And if they feel like they know you, they might be more willing to do what you want them to do” (Payton, interview, May 1, 2017). This speaks to the underlying factor to building relationships – to getting to know the voices of their student – motivation. Sydney reflected on this, stating:

I do really value building relationships with them and I definitely think that I do build a really good relationship with them . . . and it is that kind of idea that they will be more willing to do something because they like me. (Interview, May 1, 2017)

As noted by the several within the focus group, although building strong relationships with students provides a motivational influence, it is arduous. For Hailee, as she put it, “I work really hard at relationships” (Interview, May 1, 2017). Allie, in describing the end of a school week, stated, “Nothing’s available on Friday’s’ because you’re tired – because it takes so much energy . . . and that is part of your job at a rural school, I think” (Interview, May 1, 2017). Payton concurred, stating, “I’m a lot more drained at the end of the day. I think it’s because I’m having to pull on an area that’s not a natural strength” (Interview, May 1, 2017).

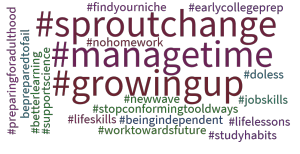

Throughout this study, as the teachers reflected on this key strategy, they described a pedagogical framework in their classrooms to engage with students in order listen to those conversations that guide instruction. Each of the educators put forth a need to change what they did in their classroom to hear the voices of their students – getting to know their touch. This engagement speaks to the underlying factor of building relationships – to getting to know the voices of their students – motivation. As noted by these rural educators, building strong relationships with students provide a motivational influence within their student but is also pedagogically demanding and time-consuming. However, all attested to the need to knowing their students’ voices due to the changing climate of the 21st-century classroom. My desire is that the findings of this research, along with this posting, will supply a voice to educators on a wider scale, providing a meaningful pedagogical framework for the 21st-century classroom.

REFERENCES

Elmore, T. (2015). Generation iY: Secrets to connecting with today’s teens & young adults in the digital age. (5th ed.). Atlanta, GA: Poet Gardener Publishing in association with Growing Leaders, Inc..

Payne, R. K. (2013). A framework for understanding poverty: A cognitive approach. (5th ed). Highlands, TX: Aha! Process, Inc.

“Despite all of my fancy degrees, I was never an educator, only an instructor . . .” (Seaton, 1948). So were the words spoken by Prof. Edward Bell, portrayed by Edmund Gwenn (think Santa Clause in Miracle on 34th Street). It was a simple, Saturday morning movie. Yet this old film snapped me back to the realities of why I teach – why educators are so important.

“Despite all of my fancy degrees, I was never an educator, only an instructor . . .” (Seaton, 1948). So were the words spoken by Prof. Edward Bell, portrayed by Edmund Gwenn (think Santa Clause in Miracle on 34th Street). It was a simple, Saturday morning movie. Yet this old film snapped me back to the realities of why I teach – why educators are so important.